Huxley Family on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Huxley family is a

*Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer.

*Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London.

*Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.

*Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer.

*Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London.

*Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.

John Collier was not a Huxley by birth, but by marriage twice over: both his wives were daughters of Thomas Henry Huxley. The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI (27 January 1850 – 11 April 1934) was a writer and painter in the

John Collier was not a Huxley by birth, but by marriage twice over: both his wives were daughters of Thomas Henry Huxley. The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI (27 January 1850 – 11 April 1934) was a writer and painter in the  Collier and his first wife Marian (Mady) had one child, Joyce, a portrait miniaturist. She married twice, first to Leslie Crawshay-Williams, whose family were South Wales ironmasters. They had two children, Rupert Crawshay-Williams and Gillian. Joyce next married Drysdale Kilburn; they had a son, Nicholas Kilburn.

By his second wife Ethel he had a daughter and a son, Sir

Collier and his first wife Marian (Mady) had one child, Joyce, a portrait miniaturist. She married twice, first to Leslie Crawshay-Williams, whose family were South Wales ironmasters. They had two children, Rupert Crawshay-Williams and Gillian. Joyce next married Drysdale Kilburn; they had a son, Nicholas Kilburn.

By his second wife Ethel he had a daughter and a son, Sir

Leonard and Julia had four children, including the biologist Julian Huxley, Sir Julian Sorell Huxley and the writer Aldous Leonard Huxley. Their middle son, Noel Trevenen (born in 1889) committed suicide in 1914. Their daughter, Margaret Arnold Huxley, was born in 1899 and died on 11 October 1981. After the death of his first wife, Leonard married Rosalind Bruce (1890–1994), and had two further sons. The elder of these was David Bruce Huxley (1915-1992), whose daughter Angela Huxley married George Pember Darwin, son of the physicist Sir

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

family; several of its members have excelled in science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

, arts

The arts are a very wide range of human practices of creative expression, storytelling and cultural participation. They encompass multiple diverse and plural modes of thinking, doing and being, in an extremely broad range of media. Both hi ...

and literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

. The family also includes members who occupied senior positions in the public service of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

.

The patriarch of the family was the zoologist and comparative anatomist Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

(1825–1895). His grandsons include Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

(author of ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarch ...

'' and ''The Doors of Perception

''The Doors of Perception'' is an autobiographical book written by Aldous Huxley. Published in 1954, it elaborates on his psychedelic experience under the influence of mescaline in May 1953. Huxley recalls the insights he experienced, rangin ...

'') and his brother Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. ...

(an evolutionary biologist and the first director of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

) and the Nobel laureate physiologist

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical a ...

Andrew Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley (22 November 191730 May 2012) was an English physiologist and biophysicist. He was born into the prominent Huxley family. After leaving Westminster School in central London, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge ...

.

Family tree

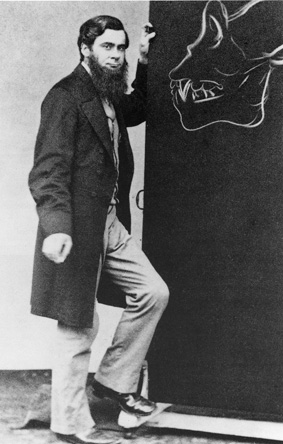

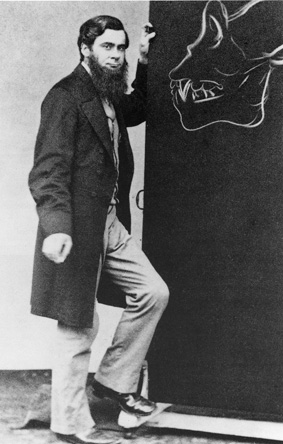

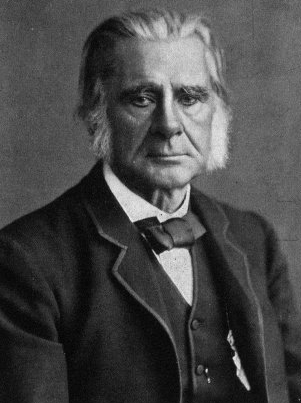

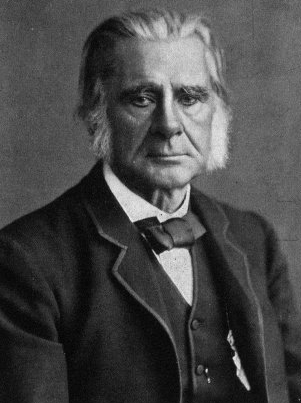

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The storie ...

(1825–1895) was an English biologist. Known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his defence of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variatio ...

. Mostly a self-educated man, he had an extraordinary influence on the British educated public. He was instrumental in developing scientific education in Britain, and opposed those Christian leaders who tried to stifle scientific debate. He was a member of eight Royal Commissions and two other commissions. A noted unbeliever

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or the irreligious.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Churc ...

, he used the term "agnostic

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

" to describe his attitude to theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

.

Though Huxley was a great comparative anatomist

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

, perhaps his most notable scientific achievement was his work on human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of ...

. Starting in 1858, Huxley gave lectures and published papers which analysed the zoological position of man. The best were collected in a landmark work: ''Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature

''Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'' is an 1863 book by Thomas Henry Huxley, in which he gives evidence for the evolution of humans and apes from a common ancestor. It was the first book devoted to the topic of human evolution, and discusse ...

'' (1863). This contained two themes: first, humans are related to the great apes, and second, the species has evolved in a similar manner to all other forms of life. These were ideas which the careful and cautious Darwin had only hinted at in ''The Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', but with which Huxley was in full agreement.

In 1855, he married Henrietta Anne Heathorn (1825–1915), an English émigrée whom he had met in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

. They had five daughters and three sons:

*Noel Huxley (1856–1860), died aged 4.

*Jessie Oriana Huxley (1858–1927), married architect Fred Waller in 1877.

*Marian Huxley

Marian "Mady" Collier ( née Marian Huxley; 1859–1887) also spelled as Marion Huxley, was a British 19th-century painter and is associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Biography

Marian Huxley was born in 1859 in London, to father Tho ...

(1859–1887) married artist John Collier in 1879.

* Leonard Huxley (1860–1933), married Julia Arnold.

*Rachel Huxley (1862–1934) married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884.

*Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer.

*Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London.

*Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.

*Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley (1863–1940), married Harold Roller, travelled Europe as a singer.

*Henry Huxley (1865–1946), became a fashionable general practitioner in London.

*Ethel Huxley (1866–1941) married artist John Collier (widower of sister) in 1889.

John Collier (son-in-law)

John Collier was not a Huxley by birth, but by marriage twice over: both his wives were daughters of Thomas Henry Huxley. The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI (27 January 1850 – 11 April 1934) was a writer and painter in the

John Collier was not a Huxley by birth, but by marriage twice over: both his wives were daughters of Thomas Henry Huxley. The Honourable John Maler Collier OBE RP ROI (27 January 1850 – 11 April 1934) was a writer and painter in the Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James ...

style. He was one of the leading portrait painters of his generation. The National Portrait Gallery's collection of his portraiture is weak, but in 2007 it bought his first wife's portrait of him painting her.

Collier's views on religion and ethics are interesting for their comparison with the views of Thomas Henry Huxley and Julian Huxley, both of whom gave Romanes lecture

The Romanes Lecture is a prestigious free public lecture given annually at the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, England.

The lecture series was founded by, and named after, the biologist George Romanes, and has been running since 1892. Over the years, ...

s on that subject. In ''The religion of an artist'' (1926) Collier explains "It he book

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

is mostly concerned with ethics apart from religion... I am looking forward to a time when ethics will have taken the place of religion... My religion is really negative. he benefits of religion

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' ...

can be attained by other means which are less conducive to strife and which put less strain on upon the reasoning faculties". On secular morality

Secular morality is the aspect of philosophy that deals with morality outside of religious traditions. Modern examples include humanism, freethinking, and most versions of consequentialism. Additional philosophies with ancient roots include those s ...

: "My standard is frankly utilitarian

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charac ...

. As far as morality is intuitive, I think it may be reduced to an inherent impulse of kindliness towards our fellow citizens". On the idea of God: "People may claim without much exaggeration that the belief in God is universal. They omit to add that superstition, often of the most degraded kind, is just as universal". And "An omnipotent Deity who sentences even the vilest of his creatures to eternal torture is infinitely more cruel than the cruellest man". And on the Church: "To me, as to most Englishmen, the triumph of Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

would mean an unspeakable disaster to the cause of civilization". His views, then, were very close to the agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

of Thomas Henry Huxley and the humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

of Julian Huxley.

Collier and his first wife Marian (Mady) had one child, Joyce, a portrait miniaturist. She married twice, first to Leslie Crawshay-Williams, whose family were South Wales ironmasters. They had two children, Rupert Crawshay-Williams and Gillian. Joyce next married Drysdale Kilburn; they had a son, Nicholas Kilburn.

By his second wife Ethel he had a daughter and a son, Sir

Collier and his first wife Marian (Mady) had one child, Joyce, a portrait miniaturist. She married twice, first to Leslie Crawshay-Williams, whose family were South Wales ironmasters. They had two children, Rupert Crawshay-Williams and Gillian. Joyce next married Drysdale Kilburn; they had a son, Nicholas Kilburn.

By his second wife Ethel he had a daughter and a son, Sir Laurence Collier

Sir Laurence Collier KCMG (1890–1976) was the British ambassador to Norway between 1939 and 1950, including the period when Norway's government was in exile in London during the Second World War.

Biography

Laurence Collier was the son of the ar ...

, (1890–1976), British Ambassador to Norway 1939–1950. In later life Ethel became known as ''The Dragon'', and then ''The Grand-Dragon'' to her grandchildren. She vetted all the family marriages; inspecting Elizabeth Powell for prospective marriage to Rupert Crawshay-Williams (her stepdaughter's son) she said "You are marrying into one of the great atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

families; I know you are an atheist now, but will you be able to keep it up until you die?". The bridegroom started working for Gramophone Records, but became a philosopher and writer. He was the author of ''The Comforts of Unreason'' (1947); ''Methods and Criteria of Reasoning'' (1957) and ''Russell Remembered'' (1970); a homage to Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

.

Ethel's daughter Joan married Captain (later General) Frank Anstie Buzzard. They had three children: John Huxley Buzzard, Richard Buzzard, and Pamela.

Collier's portraits of the family and others

Collier painted numerous portraits of members of the family. He painted both his wives, Marian (Mady) and Ethel; his children; both Thomas Henry Huxley and his wife; and many of the next two generations. A biographer reports a total of ''thirty-two'' Huxley family portraits during the half-century after his marriage to Mady. His favourite sitter was his eldest daughter Joyce, of whom six portraits are recorded. Second wife Ethel sat for four portraits; their children, Joan and Laurence, the Buzzard children, Laurence's wife Eleanor, and several of their children were also portrayed. Many of Huxley's children and some of his grandchildren were portrayed: Leonard Huxley, Julian and Juliette Huxley,Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

; Henry (Harry) Huxley and his wife, and son Gervas; Henrietta (Nettie) Huxley; and there are others.

Many scientific friends and supporters of Huxley sat for Collier. Darwin and Huxley themselves, twice each – and there were a number of replica portraits of Darwin and Huxley made by Collier. George John Romanes

George John Romanes FRS (20 May 1848 – 23 May 1894) was a Canadian-Scots evolutionary biologist and physiologist who laid the foundation of what he called comparative psychology, postulating a similarity of cognitive processes and mechanis ...

, William Kingdom Clifford

William Kingdon Clifford (4 May 18453 March 1879) was an English mathematician and philosopher. Building on the work of Hermann Grassmann, he introduced what is now termed geometric algebra, a special case of the Clifford algebra named in his ...

, Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of t ...

, William Spottiswoode

William H. Spottiswoode HFRSE LLD (11 January 1825 – 27 June 1883) was an English mathematician, physicist and partner in the printing and publishing firm Eyre & Spottiswoode. He was president of the Royal Society from 1878 to 1883.

Biogra ...

, Sir John Lubbock, E. Ray Lankester and Sir Michael Foster were all important friends. Francis Balfour and John Tyndall

John Tyndall FRS (; 2 August 1820 – 4 December 1893) was a prominent 19th-century Irish physicist. His scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the p ...

were portrayed after their tragic deaths.

Margaret Huxley (niece)

Margaret Huxley (1854–1940) was the niece of Thomas Henry Huxley, daughter of his brother William Thomas Huxley. She became a senior nurse in Dublin and is considered to be the pioneer of scientific nursing training in Ireland, after establishing nursing education in her own hospital and a few years later in a central school. She campaigned for the professionalisation of nursing and a formal system of nurse registration.Sir Leonard George Holden Huxley (distant cousin)

SirLeonard George Holden Huxley

Sir Leonard George Holden Huxley (29 May 1902 – 4 September 1988) was an Australian physicist.

Huxley was born in London, the eldest son of George Hamborough and Lilian Huxley. He was a second-cousin once removed of Thomas Huxley. His ...

KBE (1902–1988) was second cousin once removed of Thomas Henry Huxley. Much of his life was spent in Australia, though he was at Oxford from 1923 to 1930. He obtained his D.Phil

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is ...

from Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in 1928. The final period of his life was spent in Australia, University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

(1949–60); Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

(1960–67), latterly as Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and former Commonwealth n ...

. A key figure in the establishment of the Anglo-Australian Telescope

The Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) is a 3.9-metre equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia, at an altitude of a little over 1,100 m. In 2 ...

.

Leonard Huxley and issue

Leonard Huxley (1860–1933), the most prominent of T. H. Huxley's children, had six children, several of whom left their mark on the twentieth century. He was a teacher (assistant master) atCharterhouse

Charterhouse may refer to:

* Charterhouse (monastery), of the Carthusian religious order

Charterhouse may also refer to:

Places

* The Charterhouse, Coventry, a former monastery

* Charterhouse School, an English public school in Surrey

London ...

, then assistant editor and later editor of the ''Cornhill Magazine

''The Cornhill Magazine'' (1860–1975) was a monthly Victorian magazine and literary journal named after the street address of the founding publisher Smith, Elder & Co. at 65 Cornhill in London.Laurel Brake and Marysa Demoor, ''Dictiona ...

''. Huxley's major biographies were the three volumes of ''Life and Letters of Thomas Henry Huxley'' and the two volumes of ''Life and Letters of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For twenty years he served as director of t ...

OM GCSI''.

His first wife was Julia Arnold

Julia Huxley (née Arnold) (1862–1908) was a British scholar. She founded Prior's Field School for girls, in Godalming, Surrey in 1902. She came from and had an exceptional family.

Life

Born Julia Arnold in 1862 to Julia Sorell Arnold, the gra ...

(1862–1908), founder in 1902 of Prior's Field School a still existing girls' school in Godalming, Surrey. Through her Leonard was connected to the intellectual family of the Arnolds: his wife's father was Tom Arnold Tom Arnold may refer to:

* Tom Arnold (actor) (born 1959), American actor

* Tom Arnold (economist) (born 1948), Irish CEO of Concern Worldwide

* Tom Arnold (footballer) (1878–?), English footballer

* Tom Arnold (literary scholar) (1823–1900), ...

(1823–1900), who married Julia Sorell, granddaughter of a former governor of Tasmania. Julia Arnold's sister was the best-selling novelist Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

(who wrote as Mrs Humphry Ward), her uncle the poet Matthew Arnold

Matthew Arnold (24 December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic who worked as an inspector of schools. He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the celebrated headmaster of Rugby School, and brother to both Tom Arnold, lite ...

, and her grandfather the influential Rugby School

Rugby School is a public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Founded in 1567 as a free grammar school for local boys, it is one of the oldest independent schools in Britain. Up ...

headmaster Thomas Arnold

Thomas Arnold (13 June 1795 – 12 June 1842) was an English educator and historian. He was an early supporter of the Broad Church Anglican movement. As headmaster of Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, he introduced several reforms that were wide ...

. In her youth she and her sister Ethel had inspired Charles Dodgson (aka Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequel ...

) to invent doublet (now called word ladder

Word ladder (also known as Doublets, word-links, change-the-word puzzles, paragrams, laddergrams, or word golf) is a word game invented by Lewis Carroll. A word ladder puzzle begins with two words, and to solve the puzzle one must find a chain of o ...

Leonard and Julia had four children, including the biologist Julian Huxley, Sir Julian Sorell Huxley and the writer Aldous Leonard Huxley. Their middle son, Noel Trevenen (born in 1889) committed suicide in 1914. Their daughter, Margaret Arnold Huxley, was born in 1899 and died on 11 October 1981. After the death of his first wife, Leonard married Rosalind Bruce (1890–1994), and had two further sons. The elder of these was David Bruce Huxley (1915-1992), whose daughter Angela Huxley married George Pember Darwin, son of the physicist Sir

Charles Galton Darwin

Sir Charles Galton Darwin (19 December 1887 – 31 December 1962) was an English physicist who served as director of the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) during the Second World War. He was a son of the mathematician George Howard Darwin an ...

(and thus a great-grandson of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

married a great-granddaughter of Thomas Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

). The younger son (1917-2012) was the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

winner, physiologist Andrew Fielding Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley (22 November 191730 May 2012) was an English physiologist and biophysicist. He was born into the prominent Huxley family. After leaving Westminster School in central London, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge on ...

.

A Plaque was erected in 1995 at the house in Bracknell Gardens, Hampstead to commemorate Leonard, Julian and Aldous 'Men of Science and Letters, lived here.'

Sir Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley

Sir Julian Sorell Huxley (22 June 1887 – 14 February 1975) was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. He was a proponent of natural selection, and a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century modern synthesis. ...

(1887–1975) was the first Director-General of UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

. He was Secretary of Zoological Society, co-founder of the World Wildlife Fund

The World Wide Fund for Nature Inc. (WWF) is an international non-governmental organization founded in 1961 that works in the field of wilderness preservation and the reduction of human impact on the environment. It was formerly named the Wo ...

, and president of the British Eugenics Society. He won the Darwin Medal

The Darwin Medal is one of the medals awarded by the Royal Society for "distinction in evolution, biological diversity and developmental, population and organismal biology".

In 1885, International Darwin Memorial Fund was transferred to the ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, the Darwin–Wallace Medal

The Darwin–Wallace Medal is a medal awarded by the Linnean Society of London for "major advances in evolutionary biology". Historically, the medals have been awarded every 50 years, beginning in 1908. That year marked 50 years after the joint p ...

of the Linnaean Society

The Linnean Society of London is a learned society dedicated to the study and dissemination of information concerning natural history, evolution, and taxonomy. It possesses several important biological specimen, manuscript and literature colle ...

, the Kalinga Prize

The Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science is an award given by UNESCO for exceptional skill in presenting scientific ideas to lay people. It was created in 1952, following a donation from Biju Patnaik, Founder President of the Kalinga ...

and the Lasker Award

The Lasker Awards have been awarded annually since 1945 to living persons who have made major contributions to medical science or who have performed public service on behalf of medicine. They are administered by the Lasker Foundation, which was ...

. He presided over the founding conference for the International Humanist and Ethical Union

Humanists International (known as the International Humanist and Ethical Union, or IHEU, from 1952–2019) is an international non-governmental organisation championing secularism and human rights, motivated by secular humanist values. Found ...

. He wrote fifty books, including "The Science of Life

''The Science of Life'' is a book written by H. G. Wells, Julian Huxley and G. P. Wells, published in three volumes by The Waverley Publishing Company Ltd in 1929–30, giving a popular account of all major aspects of biology as known in the 1 ...

", co-authored with H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

at a time when Darwin's idea was denigrated by many. His master-work '' Evolution: The Modern Synthesis'' gave the name to a mid-century movement which united biological theory and overcame problems caused by over-specialisation.

Julian married Juliette Baillot in 1919. They had two children, and both became scientists: Anthony Julian Huxley

Anthony Julian Huxley (2 December 1920 – 26 December 1992) was a British botanist. He edited '' Amateur Gardening'' from 1967 to 1971, and was vice-president of the Royal Horticultural Society in 1991.

He was the son of Julian Huxley. He w ...

, a botanist and horticulturalist, and Francis Huxley

Francis Huxley (28 August 1923 – 29 October 2016) was a British botanist, anthropologist and author. He is a son of Julian Huxley. His brother was Anthony Julian Huxley. His uncle was Aldous Huxley.

He was one of the founders of Survival Inter ...

, an anthropologist.

A Wetherspoon

J D Wetherspoon plc (branded variously as Wetherspoon or Wetherspoons, and colloquially known as Spoons) is a pub company operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland. The company was founded in 1979 by Tim Martin and is based in Watford. It o ...

Public house in Selsdon

Selsdon is an area in South-East London, England, located in the London Borough of Croydon, in the ceremonial county of Greater London. Prior to 1965 it was in the historic county of Surrey. It is located south of Coombe and Addiscombe, west o ...

was named after him as he was one of the main backers of the Selsdon Wood Nature Reserve

Selsdon Wood is a woodland area located in the London Borough of Croydon. The park is owned by the National Trust but managed by the London Borough of Croydon. It is a Local Nature Reserve.

The wood has a Friends group - the Friends of Selsdon ...

.

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

(1894–1963) was a novelist and philosopher. His styles were iconoclasm

Iconoclasm (from Ancient Greek, Greek: grc, wikt:εἰκών, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, wikt:κλάω, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, wikt:εἰκών, εἰκών + wi ...

; disenchanted social commentary and a dystopic view of the future were repeated themes. He was regarded in California, where he spent the latter part of his life, as a considerable intellectual guru. His main works include ''Crome Yellow

''Crome Yellow'' is the first novel by British author Aldous Huxley, published by Chatto & Windus in 1921, followed by a U.S. edition by George H. Doran Company in 1922. Though a social satire of its time, it is still appreciated and has been a ...

'' (1921), '' Antic Hay'' (1923), ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarch ...

'' (1932) (which began as a parody of '' Men Like Gods'' by H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Eyeless in Gaza'' (1936) and ''

Henry Huxley, the youngest son and penultimate child of T. H. Huxley, trained in medicine at

Henry Huxley, the youngest son and penultimate child of T. H. Huxley, trained in medicine at

The eldest son of Henry Huxley, Gervas served in the

The eldest son of Henry Huxley, Gervas served in the

T. H. Huxley had periods of depression at the end of 1871, alleviated by a cruise to Egypt. And again in 1873, this time coincident with expensive building work on his house. His friends were really alarmed, and his doctor ordered three months rest. Darwin picked up his pen, and with Tyndall's help raised £2,100 for him — an enormous sum. The money was partly to pay for his recuperation, and partly to pay his bills. Huxley set out in July with Hooker to the

T. H. Huxley had periods of depression at the end of 1871, alleviated by a cruise to Egypt. And again in 1873, this time coincident with expensive building work on his house. His friends were really alarmed, and his doctor ordered three months rest. Darwin picked up his pen, and with Tyndall's help raised £2,100 for him — an enormous sum. The money was partly to pay for his recuperation, and partly to pay his bills. Huxley set out in July with Hooker to the

Island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

'' (1960). ''Island'', his last novel, is set in a utopia, in profound contrast to the dystopian ''Brave New World''. The central theme is the development of a society which unites the best of western and eastern culture. It contains, amongst more serious ideas, the humorous notion of parrots who utter uplifting slogans. Huxley also wrote many essays, including ''The Doors of Perception

''The Doors of Perception'' is an autobiographical book written by Aldous Huxley. Published in 1954, it elaborates on his psychedelic experience under the influence of mescaline in May 1953. Huxley recalls the insights he experienced, rangin ...

'' which he wrote while experimenting with mescaline

Mescaline or mescalin (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a naturally occurring psychedelic protoalkaloid of the substituted phenethylamine class, known for its hallucinogenic effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin.

Biological sou ...

. Its title was taken from a poem by William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, and in turn inspired the name of the band The Doors

The Doors were an American Rock music, rock band formed in Los Angeles in 1965, with vocalist Jim Morrison, keyboardist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger, and drummer John Densmore. They were among the most controversial and influential ro ...

.

Aldous married twice, to Maria Nys (1919), and after her death, to Laura Archera (1956). Laura felt inspired to illuminate the story of their provocative marriage through Mary Ann Braubach's 2010 documentary, "Huxley on Huxley". His only child, Matthew Huxley

Matthew Huxley (19 April 1920 – 10 February 2005) was an epidemiologist and anthropologist, as well as an educator and author. His work ranged from promoting universal health care to establishing standards of care for nursing home patients and th ...

(1920 – 10 February 2005, age 84) was also an author, as well as an educator, anthropologist and prominent epidemiologist. His work ranged from promoting universal health care to establishing standards of care for nursing home patients and the mentally ill to investigating the question of what is a socially sanctionable drug. Matthew's first marriage, to documentary filmmaker Ellen Hovde, ended in divorce. His second wife died in 1983. He was survived by his third wife, Franziska Reed Huxley; and two children from his first marriage, Trevenen Huxley and Tessa Huxley.

David Bruce Huxley

Financier and lawyer (1915–1992). He served inWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in Africa and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

reaching the rank of Brigade Major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section direct ...

in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

. He became the youngest Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of ...

(QC) in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. In Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

in the 1940s and 1950s he was Solicitor General, Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

, and acting Chief Justice of the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

. He compiled and revised many of the laws of Bermuda. He married twice and had five children by his first wife, Anne Remsen Schenck. His daughter Angela Mary Bruce Huxley (born 1939) married George Pember Darwin in 1964, and his son Michael Remsen Huxley (born 1940) became curator of science at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

. In retirement, David and his second wife, Ouida (who was raised by her aunt Ouida Rathbone, married to the actor Basil Rathbone

Philip St. John Basil Rathbone MC (13 June 1892 – 21 July 1967) was a South African-born English actor. He rose to prominence in the United Kingdom as a Shakespearean stage actor and went on to appear in more than 70 films, primarily costume ...

) lived in Wansford-in-England, Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

, where he served as churchwarden

A churchwarden is a lay official in a parish or congregation of the Anglican Communion or Catholic Church, usually working as a part-time volunteer. In the Anglican tradition, holders of these positions are ''ex officio'' members of the parish b ...

.

Andrew Huxley

Andrew Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley (22 November 191730 May 2012) was an English physiologist and biophysicist. He was born into the prominent Huxley family. After leaving Westminster School in central London, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge ...

(1917–2012), the last child of Leonard Huxley, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

for studies of the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

, especially the activity of nerve fibres

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis), or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see spelling differences), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action po ...

. He was knighted in 1974 and appointed to the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

in 1983. He was the second Huxley to be President of the Royal Society

The president of the Royal Society (PRS) is the elected Head of the Royal Society of London who presides over meetings of the society's council.

After informal meetings at Gresham College, the Royal Society was officially founded on 28 November ...

, the first being his grandfather, T. H. H.

In 1947 he married Jocelyn Richenda Gammell Pease (1925–2003), the daughter of the geneticist Michael Pease

Michael Stewart Pease OBESupplement to the London Gazette

11 June 1966, p ...

and his wife Helen Bowen Wedgwood, the daughter of 11 June 1966, p ...

Josiah Wedgwood IV

Colonel Josiah Clement Wedgwood, 1st Baron Wedgwood, (16 March 1872 – 26 July 1943), sometimes referred to as Josiah Wedgwood IV, was a British Liberal and Labour politician who served in government under Ramsay MacDonald. He was a promin ...

. They had one son and five daughters:

Janet Rachel Huxley (born 1948);

Stewart Leonard Huxley (born 1949);

Camilla Rosalind Huxley (born 1952);

Eleanor Bruce Huxley (born 1959);

Henrietta Catherine Huxley (born 1960);

Clare Marjory Pease Huxley (born 1962).

Jessie Oriana Huxley (1858–1927) and issue

Jessie, the eldest daughter of T. H. Huxley, survivedscarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

when two years old, a disease which had killed her brother Noel. She grew up to marry Frederick Waller, who became architect to the Dean and Chapter of Gloucester Cathedral

Gloucester Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Peter and the Holy and Indivisible Trinity, in Gloucester, England, stands in the north of the city near the River Severn. It originated with the establishment of a minster dedicated to S ...

and unofficial architect-in-chief to the Huxley family.

Jessie and Fred had a son, Noel Huxley Waller, and a daughter, Oriana Huxley Waller. Noel won the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

in the Gloucestershire Regiment

The Gloucestershire Regiment, commonly referred to as the Glosters, was a line infantry regiment of the British Army from 1881 until 1994. It traced its origins to Colonel Gibson's Regiment of Foot, which was raised in 1694 and later became the ...

in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, later becoming Colonel of the 5th Gloucesters, a territorial battalion of the regiment. He succeeded his father as architect to Gloucester Cathedral, and had five children from two marriages. He married, first, Helen Durrant, with Anthony, Audrey, Oriana and Letitia as children. Then he married Marion Taylor, with daughters Marion and Priscilla.

Oriana married E. S. P. Haynes

Edmund Sidney Pollock Haynes (26 September 1877 – 5 January 1949), best known as E. S. P. Haynes was a British lawyer and writer.

Biography

The son of a London solicitor, Haynes was a King's Scholar at Eton College and a winner of a Bracke ...

, an Eton Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

* Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

* Éton, a commune in the Meuse dep ...

and Balliol scholar who became a dedicated divorce law reformer. They had three daughters, Renée, Celia and Elvira. Renée Haynes, a successful novelist, married Jerrard Tickell

Edward Jerrard Tickell (14 February 1905 – 27 March 1966) was an Irish writer, known for his novels and historical books on the Second World War.

Biography

Jerrard Tickell was born in Dublin and educated in Tipperary and, from 1919 until 1922 a ...

, an Irish writer. They had three sons, one of whom, Crispin, became a distinguished civil servant. The daughter of another son, Patrick, is Dame Clare Tickell, Chief Executive of Action for Children

Action for Children (formerly National Children's Home) is a United Kingdom, UK children's charity created to help vulnerable children & young people and their families in the UK. The charity has 7,000 staff and volunteers who operate over 475 ...

. Clare Tickell's brother, Adam, was Pro Vice Chancellor at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

, which grew out of Mason Science College

Mason Science College was a university college in Birmingham, England, and a predecessor college of Birmingham University. Founded in 1875 by industrialist and philanthropist Sir Josiah Mason, the college was incorporated into the University o ...

which Thomas Huxley formally opened in 1880. Professor Adam Tickell is now Vice Chancellor at the University of Sussex.

Sir Crispin Tickell

Sir Crispin TickellGCMG

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

KCVO (25 August 1930 - 25 January 2022) is a British diplomat, academic and environmentalist. He is the great-grandson of Jessica Huxley. He was Chef de Cabinet

In several French-speaking countries and international organisations, a (French; literally 'head of office') is a senior civil servant or official who acts as an aide or private secretary to a high-ranking government figure, typically a minist ...

to the President of the European Commission

The president of the European Commission is the head of the European Commission, the executive branch of the European Union (EU). The President of the Commission leads a Cabinet of Commissioners, referred to as the College, collectively account ...

(1977–1980), British Ambassador to Mexico

The Ambassador of the United Kingdom to Mexico is the United Kingdom's foremost diplomatic representative in the United Mexican States, and head of the UK's diplomatic mission in Mexico.

Besides the embassy in Mexico City, the UK also maintains ...

(1981–1983), Permanent Secretary of the verseas Development Administration(now Department for International Development) (1984–1987), and British Ambassador to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

and Permanent Representative on the UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

(1987–1990).

Tickell was Warden of Green College, Oxford

Green Templeton College (GTC) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. The college is located on the previous Green College site on Woodstock Road next to the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter in North Oxford and ...

, between 1990 and 1997 and is director of the Policy Foresight Programme of the ''James Martin Institute for Science and Civilization'' at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

. He has been the recipient, between 1990 and 2006, of 23 honorary doctorates.

He is the president of the UK charity Tree Aid

Tree Aid is an international development non-governmental organisation which focuses on working with people in the Sahel region in Africa to tackle poverty and the effects of climate change by growing trees, improving people's incomes, and res ...

, which enables communities in Africa's drylands to fight poverty and become self-reliant, while improving the environment. He has many interests, including climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

, population issues, conservation of biodiversity and the early history of the Earth

The history of Earth concerns the development of planet Earth from its formation to the present day. Nearly all branches of natural science have contributed to understanding of the main events of Earth's past, characterized by constant geologi ...

.

His son, Oliver Tickell

Oliver Tickell is a British journalist, author and campaigner on health and environment issues, and author of the book ''Kyoto2'' which sets out a blueprint for effective global climate governance. His articles have been published in all the broa ...

, is a journalist, author and campaigner on environmental issues.

Rachel Huxley (1862–1934) and issue

Rachel Huxley, the fifth of T. H. Huxley's children, married civil engineer Alfred Eckersley in 1884, who built railways in various parts of the world. Their eldest son, Roger Huxley Eckersley, was born in Algeria; their second, Thomas Lydwell Eckersley, was born the next year. The family moved to Mexico, and their third son, Peter Eckersley, was born there. All three children married and had issue. Rachel married, secondly, Harold Shawcross, and they had two children, Betty and Anthony Shawcross. Anthony married Mary Donaldson, and they had three children, Elizabeth, Simon and David.Henry Huxley (1865–1946) and issue

Henry Huxley, the youngest son and penultimate child of T. H. Huxley, trained in medicine at

Henry Huxley, the youngest son and penultimate child of T. H. Huxley, trained in medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (died ...

, London. He married Sophy Stobart, a nurse. As she was the daughter of a considerable landowning and churchgoing family in Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

, who were somewhat nervous of a connection with the son of a famous infidel, family meetings were held to smooth feelings and avoid difficulties. After the marriage the couple were set up in London, with a medical practice for Henry.

The couple had five children: Marjorie (m. Sir E. J. Harding), Gervas (m. Elspeth), Michael (m. Ottille de Lotbinière Mills, 3c.), Christopher (m. Edmée Ritchie, 3c.) and Anne (m. Geoffrey Cooke, 3c.).

Gervas Huxley (1894–1971)

The eldest son of Henry Huxley, Gervas served in the

The eldest son of Henry Huxley, Gervas served in the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

from 1914, becoming battalion bombing officer. He received the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

on the first day of Passchendaele for capturing prisoners whose presence showed the arrival of a fresh German Guards Division. He was demobilised in 1919.

Gervas was recruited in 1939 to help set up the wartime Ministry of Information. After the war he sat on the executive committee of the British Council

The British Council is a British organisation specialising in international cultural and educational opportunities. It works in over 100 countries: promoting a wider knowledge of the United Kingdom and the English language (and the Welsh lan ...

, and became a successful author of biographies, especially on the Grosvenor family. He also penned a 1956 homage to tea, entitled "Talking of Tea". He died at Chippenham

Chippenham is a market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village ...

in 1971.

Gervas's second marriage was to Elspeth Grant (1907–1997) in 1931; she had grown up in Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

and was a friend of Joy Adamson

Friederike Victoria "Joy" Adamson ( Gessner; 20 January 1910 – 3 January 1980) was a naturalist, artist and author. Her book, ''Born Free'', describes her experiences raising a lion cub named Elsa. ''Born Free'' was printed in several langua ...

. After the marriage she wrote ''White Man's Country: Lord Delamere and the Making of Kenya''. Her life and work are the subject of a 2002 biography. As an author, Elspeth Huxley was well up to Huxley standards, and one of the few wives who was better-known than her husband. ''The Flame Trees of Thika'' (1959) was perhaps the most celebrated of her thirty books; it was later adapted for television. They had one son, Charles (1944–2015).

Mental health issues in the family

Biographers have sometimes noted the occurrence of mental illness in the Huxley family. T. H. Huxley's father became "sunk in worse than childish imbecility of mind", and later died in Barming Asylum; brother George suffered from "extreme mental anxiety" and died in 1863 leaving serious debts. Brother James was at 55 "as near mad as any sane man can be". His favourite daughter, the artistically talented Mady (Marion), who became the first wife of artist John Collier, was troubled by mental illness for years. By her mid-twenties it was becoming clear that she was not sane, and was steadily worsening (the diagnosis is uncertain). Huxley persuadedJean-Martin Charcot

Jean-Martin Charcot (; 29 November 1825 – 16 August 1893) was a French neurology, neurologist and professor of anatomical pathology. He worked on hypnosis and hysteria, in particular with his hysteria patient Louise Augustine Gleizes. Charcot ...

, one of Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating pathologies explained as originating in conflicts in ...

's teachers, to examine her with a view to treatment; but soon Mady died of pneumonia.

About T. H. Huxley himself we have a more complete record. As a young apprentice to a physician, he was taken to watch a post-mortem dissection. Afterwards he sank into a 'deep lethargy' and though he ascribed this to dissection poisoning, Cyril Bibby

Cyril Bibby (''b.'' Liverpool, 1 May 1914 as Harold Cyril Bibby; ''d''. Edinburgh 20 June 1987) was a biologist and educator. He was also one of the first sexologists.

Early life, family, etc.

Bibby was the third of eight children and lived in ...

and others have suggested that emotional shock precipitated a clinical depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD), also known as clinical depression, is a mental disorder characterized by at least two weeks of pervasive low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. Introdu ...

. The next episode we know of in his life was on the third voyage of HMS ''Rattlesnake'' in 1848. This voyage was mostly to New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and the NE Australian coast, including the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef is the world's largest coral reef system composed of over 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching for over over an area of approximately . The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland, ...

, which is a kind of wonderland for any zoologist, especially a young man hoping to make his career. The story is clear from the diary Huxley kept: p112 'little interest in the Barrier Reef'; p116 'two entries in seven weeks'; p117 '3 months passed and no journal' p124 'the black months of struggle and depression'. For him to pass up such a golden opportunity speaks of his state of mind.

T. H. Huxley had periods of depression at the end of 1871, alleviated by a cruise to Egypt. And again in 1873, this time coincident with expensive building work on his house. His friends were really alarmed, and his doctor ordered three months rest. Darwin picked up his pen, and with Tyndall's help raised £2,100 for him — an enormous sum. The money was partly to pay for his recuperation, and partly to pay his bills. Huxley set out in July with Hooker to the

T. H. Huxley had periods of depression at the end of 1871, alleviated by a cruise to Egypt. And again in 1873, this time coincident with expensive building work on his house. His friends were really alarmed, and his doctor ordered three months rest. Darwin picked up his pen, and with Tyndall's help raised £2,100 for him — an enormous sum. The money was partly to pay for his recuperation, and partly to pay his bills. Huxley set out in July with Hooker to the Auvergne

Auvergne (; ; oc, label=Occitan, Auvèrnhe or ) is a former administrative region in central France, comprising the four departments of Allier, Puy-de-Dôme, Cantal and Haute-Loire. Since 1 January 2016, it has been part of the new region Auverg ...

, and his wife and son Leonard joined him in Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western States of Germany, state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the List of cities in Germany by population, fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 m ...

, while the younger children stayed at Down House

Down House is the former home of the English naturalist Charles Darwin and his family. It was in this house and garden that Darwin worked on his theory of evolution by natural selection, which he had conceived in London before moving to Down ...

in Emma Darwin

Emma Darwin (; 2 May 1808 – 2 October 1896) was an English woman who was the wife and first cousin of Charles Darwin. They were married on 29 January 1839 and were the parents of ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.

Early lif ...

's care.

Finally, in 1884 T. H. Huxley sank into another depression, and this time it precipitated his decision to retire in 1885, at age 60. He resigned the Presidency of the Royal Society in mid-term, the Inspectorship of Fisheries, and his chair as soon as he decently could, and took six months' leave. His pension was a fairly handsome £1500 a year.

This is enough to indicate the way depression (or perhaps a moderate bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of depression and periods of abnormally elevated mood that last from days to weeks each. If the elevated mood is severe or associated with ...

) interfered with his life, but he was able to function well at other times.

The problems continued sporadically into the third generation. Two of Leonard's sons suffered serious depression: Trevenen committed suicide in 1914 and Julian suffered a number of breakdowns. Of course, there are many family members for whom no information one way or the other is available, but both the talent and the mental problems would have interested Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

: "The direct result of this enquiry is... to prove that the laws of heredity are as applicable to the mental faculties as to the bodily faculties".

Huxley Family Foundation

The Huxley Family Foundation was created by Laura Archera in 2007 to continue the work of deceased Huxley Family members and associates, as well as to work in association with the Thomas Henry Huxley X Club. Cofounders include Laura and Aldous Huxley's nephew Piero Ferrucci, his two sons, Jonathan and Emilio, andPaul Fleiss

Paul Murray Fleiss (September 8, 1933 – July 19, 2014) was an American pediatrician and author known for his unconventional medical views. Fleiss was a popular and sought-after pediatrician in the Greater Los Angeles area, both among poor and m ...

.Laura Archera Huxley Memorial, Philosophical Research Society, Los Feliz, 2008

See also

*Darwin–Wedgwood family

The Darwin–Wedgwood family are members of two connected families, each noted for particular prominent 18th-century figures: Erasmus Darwin, a physician and natural philosopher, and Josiah Wedgwood, a noted potter and founder of the eponymous ...

* Intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, the development, and the exercise of the intellect; and also identifies the life of the mind of the intellectual person. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''inte ...

* ''Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature

''Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'' is an 1863 book by Thomas Henry Huxley, in which he gives evidence for the evolution of humans and apes from a common ancestor. It was the first book devoted to the topic of human evolution, and discusse ...

''

References

{{reflist, 2 Medical families Scientific families